We failed the Trolley Problem

The government didn't just pull the wrong lever when it locked down, it wasn't honest about the bodies on the tracks ahead.

‘The Trolley’ is the insulting soubriquet given to Boris Johnson by Dominic Cummings. It was supposed to call to mind one of those wonky, annoying shopping trolleys that swerves all over the place through the supermarket aisles. In other words, chaos and incompetence.

Yet it was Johnson himself who first said ‘I’m veering all over the place like a shopping trolley,’ regarding his indecision over whether the UK should leave or remain in the EU. It’s actually not such an insulting analogy - the implication was that he could see both sides of the story.

If only he had remained a wonky trolley during the Covid pandemic, interested in the pros and cons of lockdown. You see, in another trolley analogy, the UK government failed what is known as the Trolley Problem, by refusing to be clear about the advantages and disadvantages of different options.

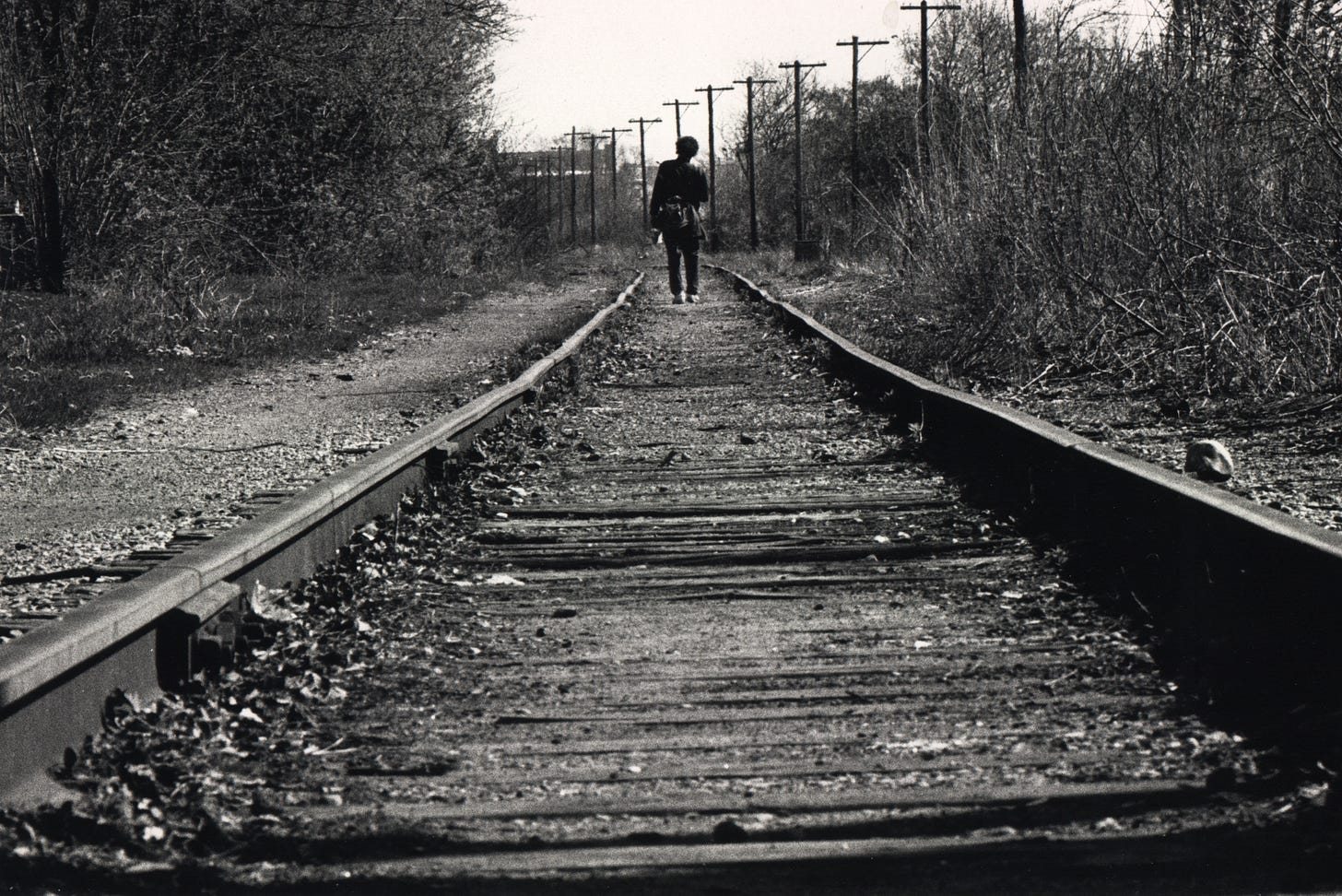

In The Trolley Problem the driver of a runaway tram (a trolley) has the choice of saving five men who are working on the track, but he will have to pull a lever to divert the trolley to another track upon which one man is working. Therefore, actively pulling the lever will still kill a man.

When considering this moral dilemma, most people would rationally choose a utilitarian approach and divert the trolley to kill one workman, thereby save a net four lives. Of course in real life, people often find it difficult to actively harm others, even if it would be outweighed by a positive benefit. After all, pulling the lever in the trolley problem does constitute an active moral decision to kill one man. Maybe it’s easier to leave the lever alone.

The Trolley Problem is simplistic and does not allow for multiples tracks and levers, nor breaks, nor even to shout at the men to move out of the way. In a vastly more complex real world model, how should the government have considered the lives to be saved by lockdown, versus the lives ended by lockdown?

‘For every Covid-19 death we would estimate another four deaths over two to five years.’ - Professor Lucy Easthope

In fact, the UK government was very quiet about acknowledging that any harms at all were attached to lockdowns, let alone deaths. To be fair, the Chief Medical Officer, Chris Whitty, did say early on that pandemics kill people in two ways: directly and indirectly, via panic and disruption. But while models were produced to impress the severity and scale of the potential deaths caused by Covid, the costs of lockdown were not calculated and communicated.

In November 2020, Tory lockdown rebels united to form the Covid Recovery Group to demand that the government provide a cost benefit analysis of lockdowns before votes on further restrictions. It seems quite astonishing looking back that no cost benefit analysis had been provided before that date. Some said it was too difficult, that better information on ‘smaller measures’ should be made public, such as the length of time people needed to quarantine, but that a cost benefit analysis of lockdown was scarcely possible.

On the 30th November 2020, the government produced a very thin and rather embarrassing attempt at a cost benefit analysis, which made little attempt to evaluate the costs to wellbeing, mental health and the economy as result of imposing restrictions, and it certainly made no attempt to weigh the costs of different courses of action. It appeared to be produced to continue to justify ongoing restrictions.

New research published this month by the Institute of Economic Affairs has concluded that lockdown policies did little to reduce Covid mortality. Scientists from Johns Hopkins University and Lund University assessed almost 20,000 studies and conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the most robust 22 studies on measures taken to protect populations against Covid across the world. The authors conclude that the draconian measures had a ‘negligible impact’ on Covid mortality and were a ‘policy failure of gigantic proportions’.